What do we talk about when we talk about Russia?

Russia, Russia, Russia—the country, it seems, is on everyone’s lips these days. One’s political affiliation doesn’t matter. The questions swirl. Did they, or didn’t they impact our electoral system? And if so, to what end? I am as interested in the answers as anyone but have none for you. So why am I writing this blog post? Because it may be useful to simply remind my readers some facts about Russia and why, no matter how it entered our heated political discourse, knowing about Russia’s history and Putin matters.

I have a visceral reaction to benign comments about Russia. Having been born in the Soviet Empire during WWII I, and especially my parents, experienced Russia’s policies on our own skin. Sometimes my emotions are mixed. I like the sound of the Russian language, one of the earliest languages I heard. Something melts inside me when I hear Russian songs, so full of longing and sadness. I smile when I think of my daughter’s Russian nesting dolls. But that’s where my warm and fuzzies stop.

My parents, who were in the minority that survived the Soviet gulags, suffered extreme deprivation, starvation, diseases and physical punishments. They were part of 20 million Russian citizens and residents imprisoned by their own government for crimes they did not commit. According to accounts by the writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn, himself a famous Gulag inmate, the number was much higher, perhaps 40-50 million. How is it possible that so many were accused? The full answer is complex, but the best and shortest answer is: paranoia.

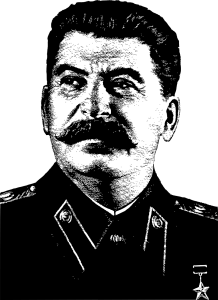

Joseph V. Stalin; Soviet dictator (1929-1953)

Joseph Stalin who loomed so large in my young life was a murderous paranoid leader who suspected everyone of opposition.

Many books have been written about the Great Terror he unleashed in the 1936-1938 period so for this blog, it’ll suffice to remind readers that he ordered the murder of one million citizens. One million is a conservative estimate by some historians. And who did he target? Intellectuals, journalists, poets, writers, the elites, ethnic minorities and “kulaks,” peasants who were said to own too much property. How did Stalin’s minions obtain the “confessions” that were touted in show trials? Often, waterboarding and other methods of torture, and always deprivation of food and sleep, and beatings. Who led these massive actions to suppress descent, real or imagined? The NKVD, Soviet Secret police.

Why am I highlighting the NKVD? For two reasons. First, I know of it from my father’s experience. If you read “In the Unlikeliest of Places: How Nachman Libeskind Survived the Nazis, Gulags and Soviet Communism,” you might recall how my father was pursued, imprisoned, beaten, threatened and harassed by the NKVD in their effort to extract from him a false confession. But the main reason I am reminding my readers about the NKVD, the forerunner of KGB, is that Vladimir Putin, about whom we have been reminded so often lately, is a product of this agency.

It was bad news to run into men wearing these caps

At age 18 Vladimir Putin entered the law department of the Leningrad State University which became an elite spy school. He was targeted by the KGB for recruitment even before he graduated. Putin was trusted enough to be posted to Dresden, Germany where his job was to recruit likely spies with “good” covers stories: journalists and academics who had credible reasons to travel to the West. By all accounts Putin excelled in his job. Even back then one of Putin’s primary interests was to recruit agents who would be trained in wireless communications and in stealing Western technology. Adding to Putin’s knowledge of and experience with intelligence was his close work with the German Stasi agency which was located just across from Putin’s office in Dresden.

When in 1999 Putin was plucked by Boris Yeltsin (then President) from the Soviet secret police and appointed to the position of Prime Minister he had never held public office. His loyalty to his former employer never waned. The Washington Post reported that during a meeting in Moscow with a PEN group of writers discussing the Great Terror of 1937, Putin stated, “…All the 17 years of my work are connected with this organization (KGB). It would be insincere for me to say that I don’t want to defend it.” No doubt, this is why he remade it into what today is known as the Federal Security Service (FSB) and became its first director.

But don’t think this is just old history. In September, 2016, a journalist Owen Matthews wrote in Politico,

“…Over Putin’s years in power, not just the Kremlin but almost every branch of the Russian state has been taken over by old KGB men like himself. Last week news broke that their resurgence is soon to be topped off with a final triumph — the resurrection of the old KGB itself. According to the Russian daily Kommersant, a major new reshuffle of Russia’s security agencies is under way that will unite the FSB (the main successor agency to the KGB) with Russia’s foreign intelligence service into a new super-agency called the Ministry of State Security — a report that, significantly, wasn’t denied by the Kremlin or the FSB itself.

The new agency, which revives the name of Stalin’s secret police between 1943 and 1953, will be as large and powerful as the old Soviet KGB, employing as many as 250,000 people.”

Let us remember well two things: that Putin has nearly two decades of experience as a spy in Soviet KGB’s foreign intelligence wing and that he once famously said, “There is no such thing as a former KGB man.” And also, do not forget that the KGB’s main mission had always been to protect those in power, not the citizenry. If you think that a leopard can change his spots, I have a bridge I can sell you.

Annette Libeskind Berkovits is the author of, “In the Unlikeliest of Places: How Nachman Libeskind Survived the Nazis, Gulags and Soviet Communism,” and “Confessions of an Accidental Zoo Curator” which will be released in April, 2017.

Please visit her website: annetteberkovits.com for more information and a list of readings/signings